Playing chess like humans

01 Aug 2020In his 1990 paper, “Elephants Don’t Play Chess”, Rodney Brooks noted that while AI agents are very good at chess, they succeed through deep search in a sort of brute force method; they do not play by chunking, strategizing, and learning like humans do. How would you create an AI agent that plays chess more like a human does?”

In 1997, Deep Blue achieved victory against then reigning chess world champion Garry Kasparov following a 4-2 defeat the previous year. But, despite its victory, Deep Blue was merely a very fast number-crunching program - it found moves by sheer brute force. As Rodney noted, modern chess programs completely rely on deep search trees and are not a “human-style” solution that would generalize well to other problems. The problem at hand is to develop an AI agent that could play chess like humans. This is important because if we could develop such an agent, then perhaps we can extrapolate the same agent to play games like GO where algorithms like deep search simply don’t scale up enough.

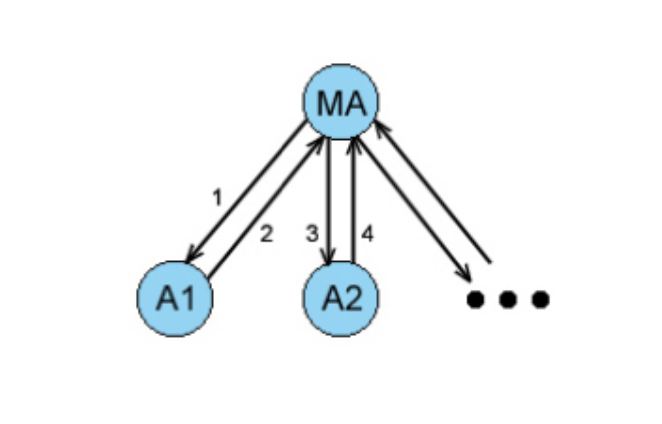

The whole state space for chess is enormous - it can be roughly estimated as 1043 (Shannon number). More than that what makes playing chess human-like difficult for an AI agent is that it requires more than a punctual coordination between two pieces at a given time. If we consider all the individual pieces on a chessboard as individual AI agents which are then being controlled by a master agent (a model very similar to the master-slave model of communication) then a very difficult challenge is to find winning chess board states as the agents individually are totally open and not enough threatened by the opponent to make them react intelligently. More on this later.

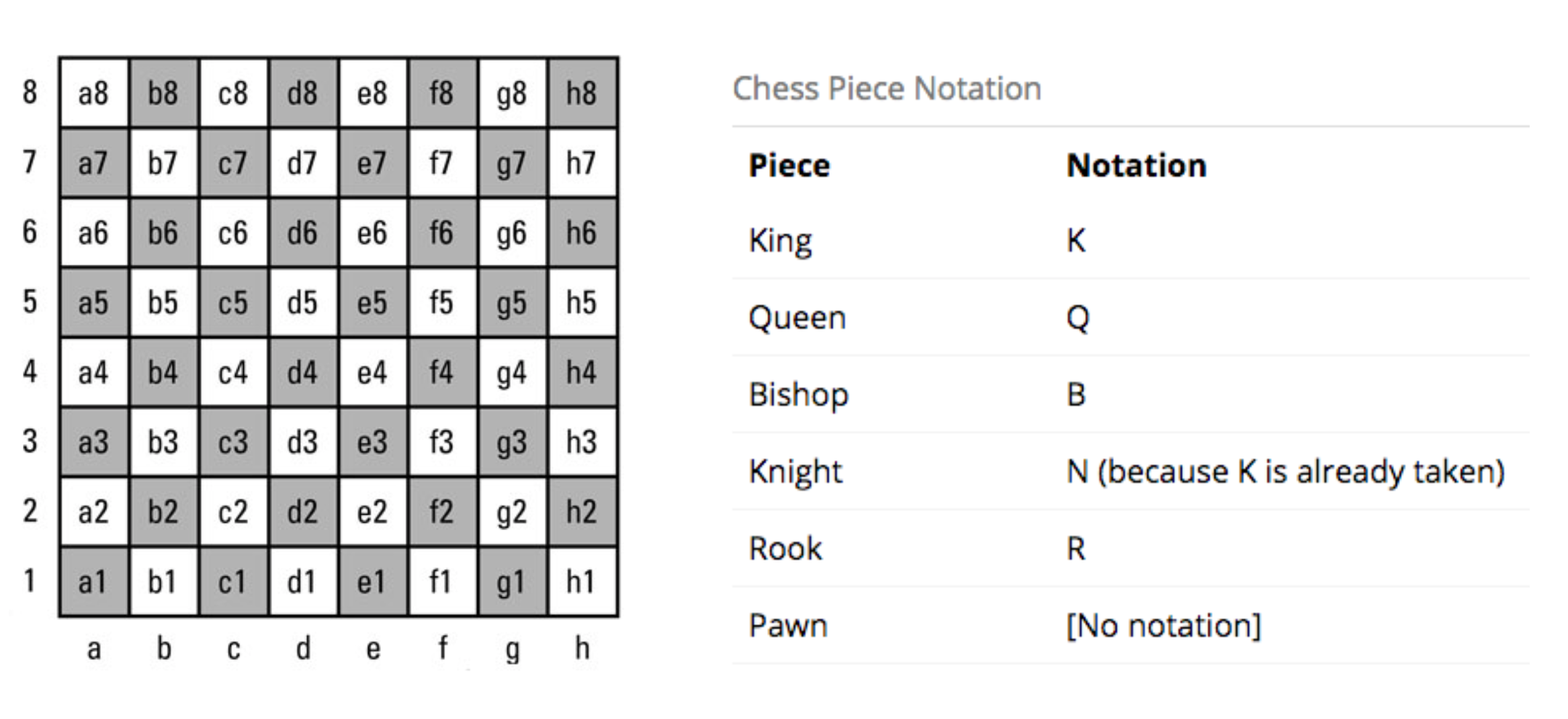

Before starting with my AI agent’s design, let’s look at the widely used basic notations in chess:

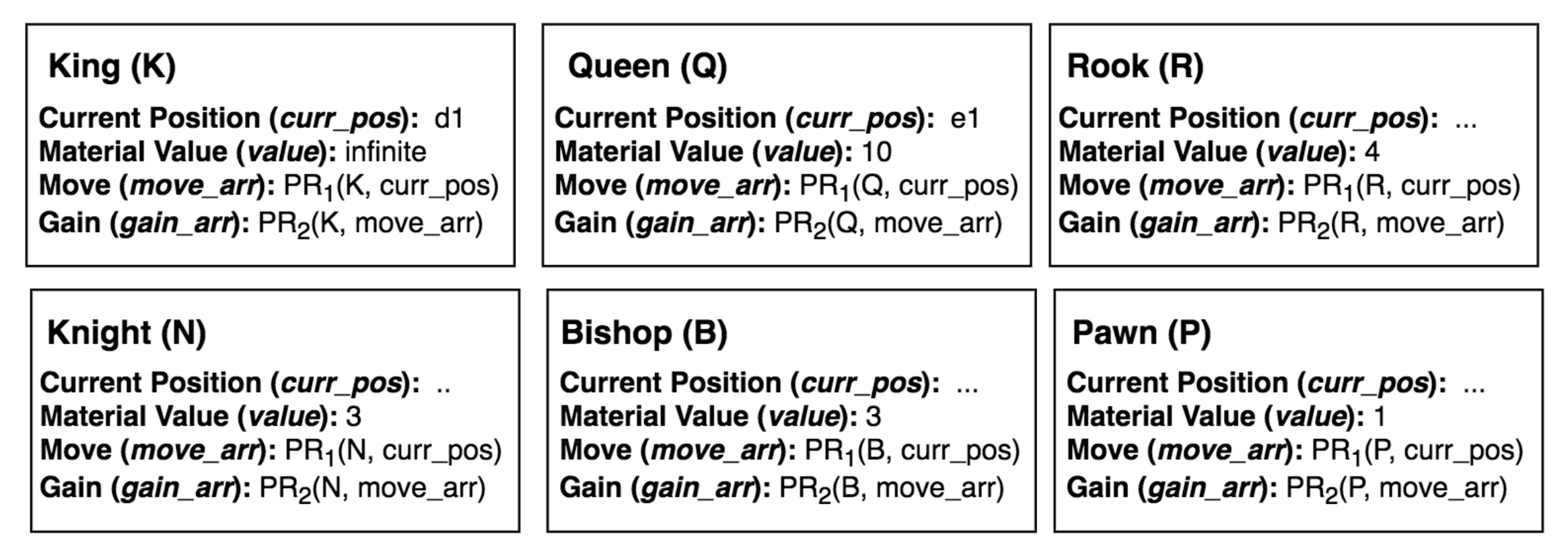

I consider each chess piece as an autonomous agent - with its own behavior and its own perception area. I then have 6 different types of agents: 8 pawns, 2 knights, 2 bishops, 2 rooks, 1 queen and 1 king. Let’s represent the knowledge associated with each of these agents as frames for the AI agent:

The current position stores the position of the chess piece on the chess board. The material value signifies the importance of the chess piece in the game – more the value more important the chess piece. Move stores the set of possible moves that the chess piece can make which are returned by a production rule. Gain stores the gains(can be negative) on making the corresponding move in the move_arr. This also maps to a production system which will consider a few production rules while deciding the profitability of a move:

- If move is an attack then profit is the material value of the opponent’s piece being attacked.

- If move is in response to a threat on our own piece then profit is the material value of our chess piece being saved from the opponent’s attack. (At a more complex level we may also want to factor in the cost - if moving this piece out of threat is putting any of our other pieces in threat)

- If move is simple a move in plan of a future attack then profit is the material value of the opponent’s piece being planned to be attacked scaled down by some factor.

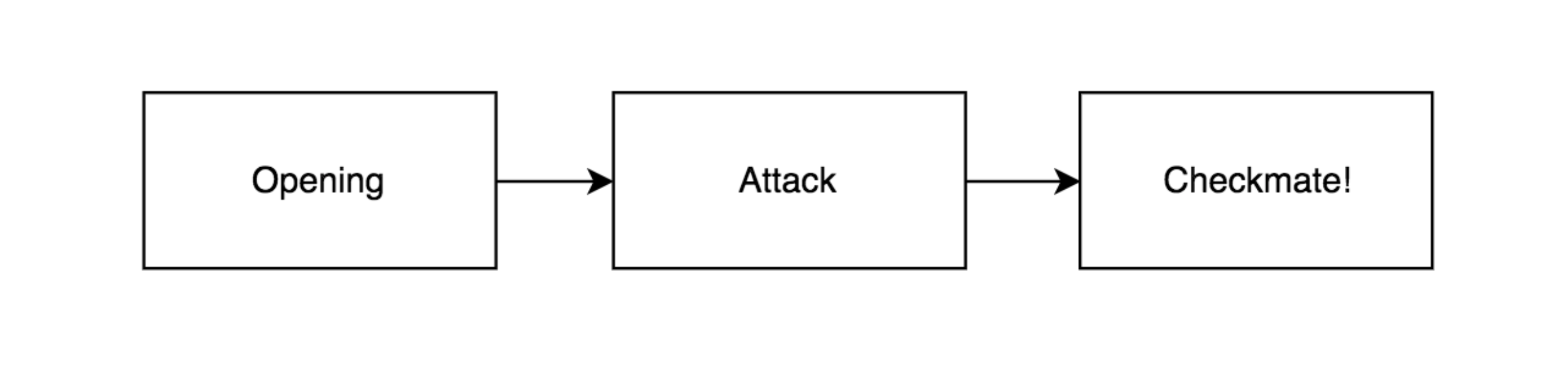

The frame for each chess piece represents the structural knowledge related to each type of chess piece. Here, the production rules act as atoms contributing to the frame – molecule. Now that I have an idea around the procedural and semantic parts of my AI’s cognitive system, let’s look at building a mechanism for episodic memory next. But before that I would like to point out that I have divided my agent’s cognition into 3 modes as shown below. This is in close connection with how human cognition for an average chess player works - they know of a few good openings, then they move on to greedily attack as many of the opponent’s pieces as possible and finally when there are a few pieces left on the board they try to think of a way to checkmate!

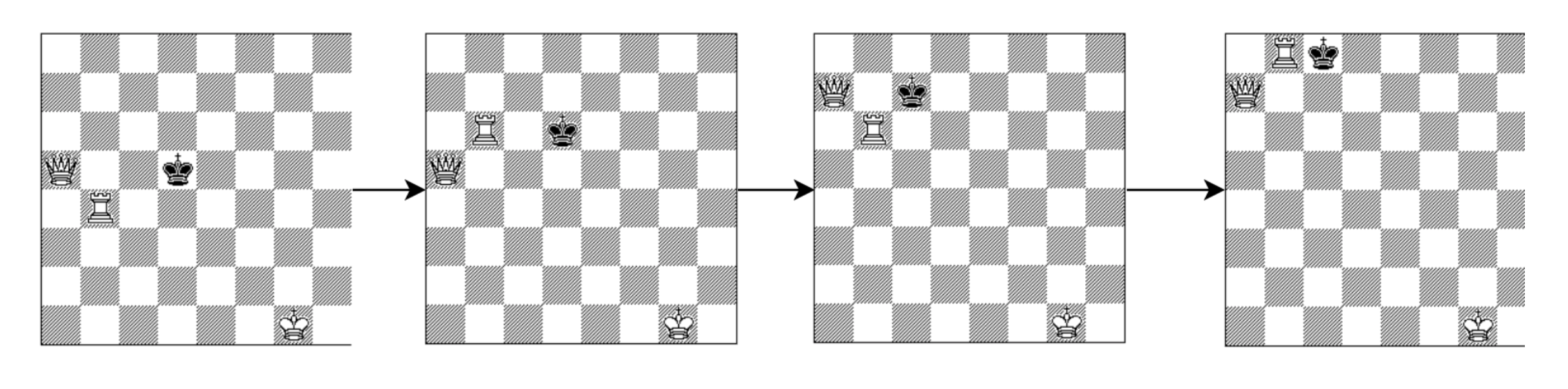

Let’s target checkmate first! Goal in chess is to checkmate – a game position in which opponent’s king is threatened with capture and there is no way to remove the threat. There are certain well-known patterns in chess from where getting a checkmate is fixed well-defined steps. To start with we can build an AI agent that continuously works towards getting close to one of the game states as defined by the patterns. For example, 1 rook and 1 queen checkmate pattern:

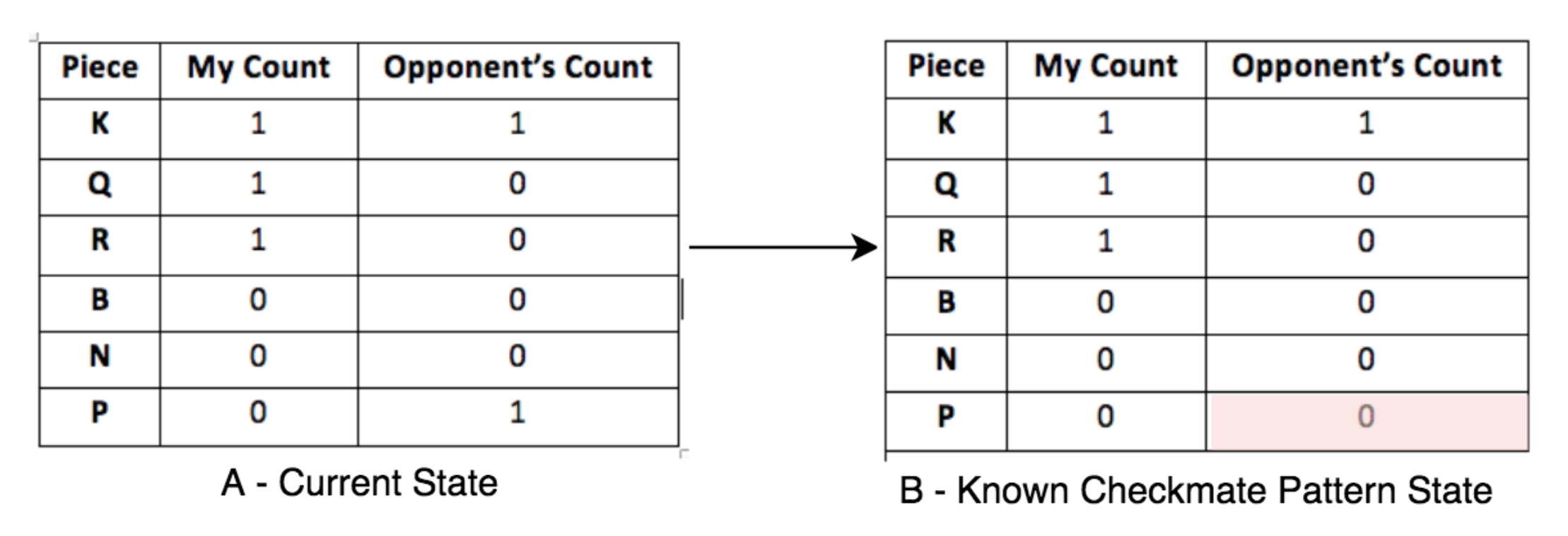

So, if we have a game state where the opponent has a king and a pawn and we have a rook, a queen and a king then this state is very close to the starting state of the 1 rook and 1 queen checkmate pattern – we just need to get rid of the opponent’s pawn. This can be represented as (storage by indexing):

Retrieval: If we represent this as a line with start point as (K,Q,R,B,N,P)my_count and end point as (K,Q,R,B,N,P)opponent_count. We can represent state A as a line in a six dimensional space from (1,1,1,0,0,0) to (1,0,0,0,0,1) and state B as a line from (1,1,1,0,0,0) to (1,0,0,0,0,0) and then use k-nearest neighbors to find the nearest known checkmate pattern state from the current state.

Adaptation: Once we find the nearest known checkmate pattern state (state B in our case which represents the 1 rook and 1 queen checkmate pattern) - we try moving to adapt to that from our present state because once we get to state B we know the next steps to checkmate. (recursive case based adaptation model)

Evaluation: In this phase, we try to execute the suggestion made as an output from the adaptation stage. In our example, it will be to attack the opponent’s pawn. We need to evaluate if it is possible to do so – it maybe that that opponent’s pawn is just a row away from our first rank and will get promoted to another piece of the opponent’s choice in the next move. So, if there is no way to attack the pawn in this move then we cannot execute our strategy and we will have to go back to the adaptation phase.

Storage: I suggested the storage by indexing method above – although this would be a bit computationally expensive in a six dimensional space.

We can use the same cased-based reasoning steps outline above for the opening – there are a fix set of openings that can be defined as good chess openings. Next, let’s discuss an approach for the attack module.

Going back to my description of all chess pieces being individual agents governed by a master agent – we can come up with a logic where all individual agents are only concerned with themselves. They check which moves and attack they can perform and which opponent pieces are threatening them. Each of these individual agents then returns its preferred move to the master agent who either performs the most valuable attack or if any of the slave agents is threatened and no attack moves seems to compensate for its lost, the threatened slave agent’s best actions are considered.

One of the challenges with the above AI agent is transitioning from opening to attack and then to checkmate. One simple heuristic can be – first x moves optimize to a known good opening, followed by all attack moves until there are < y pieces left on the chess board and finally optimizing to known checkmate design patterns. This heuristic closely relates to how an average chess player thinks and plays. Of course, our aim was not to obtain a chessmaster. Actual chess masters seem to just remember all the games that they’ve previously played. So, they have strong memorization.